1.1 When to use asyncio?

Asyncio is a library to write concurrent code using the async/await syntax. It is a single-threaded, single-process design that is ideal for I/O-bound and high-level structured network code. It is not suitable for CPU-bound code, which is better handled by the multiprocessing module.It is used for :

2.1 Coroutine

Think of a coroutine like a regular Python function but with the superpower that it can pause its execution when it encounters an operation that could take a while to complete. When that long-running operation is complete, we can “wake up” our paused coroutine and finish executing any other code in that coroutine. While a paused coroutine is waiting for the operation it paused for to finish, we can run other code. This running of other code while waiting is what gives our application concur rency. We can also run several time-consuming operations concurrently, which can give our applications big performance improvements. To both create and pause a coroutine, we’ll need to learn to use Python’s async and await keywords. The async keyword will let us define a coroutine; the await key word will let us pause our coroutine when we have a long-running operation.

2.2 Creating a coroutine with async

creating a coroutine is straightforward and not much different from creating a nor mal Python function. The only difference is that, instead of using the def keyword, we use async def. The async keyword marks a function as a coroutine instead of a nor mal Python function.

import asyncio

async def mero_coroutine():

print("Hello From Asyncio")

The coroutine in the preceding listing does nothing yet other than print “Hello world!” It’s also worth noting that this coroutine does not perform any long-running operations; it just prints our message and returns. This means that, when we put the coroutine on the event loop, it will execute immediately because we don’t have any blocking I/O, and nothing is pausing execution yet. This syntax is simple, but we’re creating something very different from a plain Python function. To illustrate this, let’s create a function that adds one to an integer as well as a coroutine that does the same and compare the results of calling each. We’ll also use the type convenience function to look at the type returned by calling a corou tine as compared to calling our normal function.

def add_function(a,b):

return a+b

async def add_coroutine(a,b):

return a+b

function=add_function(1,2)

coroutine=add_coroutine(1,2)

print(type(function))

print(type(coroutine))

When we run this code, we’ll see output like the following

Method result is 3 and the type is <class 'int'>

Coroutine result is <coroutine object coroutine_add_one at 0x1071d6040> and

the type is <class 'coroutine'>

Notice how when we call our normal add_one function it executes immediately and returns what we would expect, another integer. However, when we call coroutine_ add_one we don’t get our code in the coroutine executed at all. We get a coroutine object instead. This is an important point, as coroutines aren’t executed when we call them directly. Instead, we create a coroutine object that can be run later. To run a corou tine, we need to explicitly run it on an event loop. So how can we create an event loop and run our coroutine?

In versions of Python older than 3.7, we had to create an event loop if one did not already exist. However, the asyncio library has added several functions that abstract the event loop management. There is a convenience function, asyncio.run, we can use to run our coroutine. This is illustrated in the following listing.

import asyncio

async def add_coroutine(a,b):

return a+b

res=asyncio.run(add_coroutine(1,2))

print(res)

When we run this code, we’ll see output like the following:

3

We’ve properly put our coroutine on the event loop, and we have executed it! asyncio.run is doing a few important things in this scenario. First, it creates a brand-new event. Once it successfully does so, it takes whichever coroutine we pass into it and runs it until it completes, returning the result. This function will also do some cleanup of anything that might be left running after the main coroutine fin ishes. Once everything has finished, it shuts down and closes the event loop. Possibly the most important thing about asyncio.run is that it is intended to be the main entry point into the asyncio application we have created. It only executes one coroutine, and that coroutine should launch all other aspects of our application. As we progress further, we will use this function as the entry point into nearly all our applications. The coroutine that asyncio.run executes will create and run other coroutines that will allow us to utilize the concurrent nature of asyncio.

2.3 Pausing execution with the await keyword

The example we saw in block 2.2 did not need to be a coroutine, as it executed only non-blocking Python code. The real benefit of asyncio is being able to pause execu tion to let the event loop run other tasks during a long-running operation. To pause execution, we use the await keyword. The await keyword is usually followed by a call to a coroutine (more specifically, an object known as an awaitable, which is not always a coroutine; we’ll learn more about awaitables later in the chapter). Using the await keyword will cause the coroutine following it to be run, unlike calling a coroutine directly, which produces a coroutine object. The await expression will also pause the coroutine where it is contained in until the coroutine we awaited finishes and returns a result. When the coroutine we awaited finishes, we’ll have access to the result it returned, and the containing coroutine will “wake up” to handle the result. We can use the await keyword by putting it in front of a coroutine call. Expanding on our earlier program, we can write a program where we call the add_coroutine function inside of a “main” async function and get the result

import asyncio

async def add_one(number: int) -> int:

return number + 1

async def main() -> None:

one_plus_one = await add_one(1) # Pause, and wait for the result of add_one(1).

two_plus_one = await add_one(2) # Pause, and wait for the result of add_one(2).

print(one_plus_one)

print(two_plus_one)

asyncio.run(main())

Note: Coroutine will only run when we use

awaitkeyword. If we call the coroutine directly it will return a coroutine object.

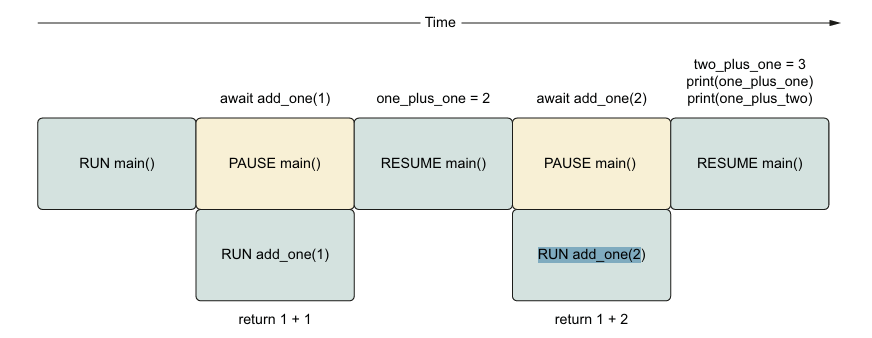

In above code we pause execution twice. We first await the call to add_one(1). Once we have the result, the main function will be “unpaused,” and we will assign the return value from add_one(1) to the variable one_plus_one, which in this case will be two. We then do the same for add_one(2) and then print the results.We can visualize the execution flow of our application, as shown in figure

As it stands now, this code does not operate differently from normal, sequential code. We are, in effect, mimicking a normal call stack. Next, let’s look at a simple example of how to run other code by introducing a dummy sleep operation while we’re waiting.

2.4 Introducing long-running coroutines with sleep

Our previous examples did not use any slow operations and were used to help us learn the basic syntax of coroutines. To fully see the benefits and show how we can run mul tiple events simultaneously, we’ll need to introduce some long-running operations. Instead of making web API or database queries right away, which are nondeterministic as to how much time they will take, we’ll simulate long-running operations by specify ing how long we want to wait. We’ll do this with the asyncio.sleep function. We can use asyncio.sleep to make a coroutine “sleep” for a given number of sec onds. This will pause our coroutine for the time we give it, simulating what would hap pen if we had a long-running call to a database or web API. asyncio.sleep is itself a coroutine, so we must use it with the await keyword. If we call it just by itself, we’ll get a coroutine object. Since asyncio.sleep is a coroutine, this means that when a coroutine awaits it, other code will be able to run. Let’s examine a simple example, shown in the following listing, that sleeps for 1 sec ond and then prints a ‘Hello World!’ message.

import asyncio

async def hello_world_message():

await asyncio.sleep(1)

print("Hello World")

asyncio.run(hello_world_message())

When we run this application, our program will wait 1 second before printing our ‘Hello World!’ message. Since hello_world_message is a coroutine and we pause it for 1 second with asyncio.sleep, we now have 1 second where we could be running other code concurrently.

We’ll be using sleep a lot in the next few examples, so let’s invest the time to cre ate a reusable coroutine that sleeps for us and prints out some useful information. We’ll call this coroutine delay. This is shown in the following listing

import asyncio

async def delay(delaysecond):

print(f'Sleeping for delay seconds : {delaysecond}')

await asyncio.sleep(delaysecond)

print(f'finished sleeping for {delay_seconds} second(s)')

return delay_seconds

```bash

delay will take in an integer of the duration in seconds that we’d like the function to

sleep and will return that integer to the caller once it has finished sleeping. We’ll also

print when sleep begins and ends. This will help us see what other code, if any, is run

ning concurrently while our coroutines are paused.

To make referencing this utility function easier in future code listings, we’ll create

a module that we’ll import in the remainder of this book when needed. We’ll also add

to this module as we create additional reusable functions. We’ll call this module util,

and we’ll put our delay function in a file called delay_functions.py. We’ll also add

an __init__.py file with the following line, so we can nicely import the timer

from util.delay_functions import delay

From now on in this book, we’ll use from util import delay whenever we need to use

the delay function. Now that we have a reusable delay coroutine, let’s combine it with

the earlier coroutine add_one to see if we can get our simple addition to run concur

rently while hello_world_message is paused.

```python

import asyncio

from util.delay_functions import delay

async def add_one(number):

return number + 1

async def hello_world_message():

await delay(1)

print("Hello World")

async def main() -> None:

message = await hello_world_message() #pause until hello_world_message is finished

one_plus_one = await add_one(1) #pause until add_one is finished

print(one_plus_one)

print(message)

asyncio.run(main())

```bash

When we run this, 1 second passes before the results of both function calls are

printed. What we really want is the value of add_one(1) to be printed immediately

while hello_world_message()runs concurrently. So why isn’t this happening with this

code? The answer is that await pauses our current coroutine and won’t execute any

other code inside that coroutine until the await expression gives us a value. Since it

will take 1 second for our hello_world_message function to give us a value, the main

coroutine will be paused for 1 second. Our code behaves as if it were sequential in this

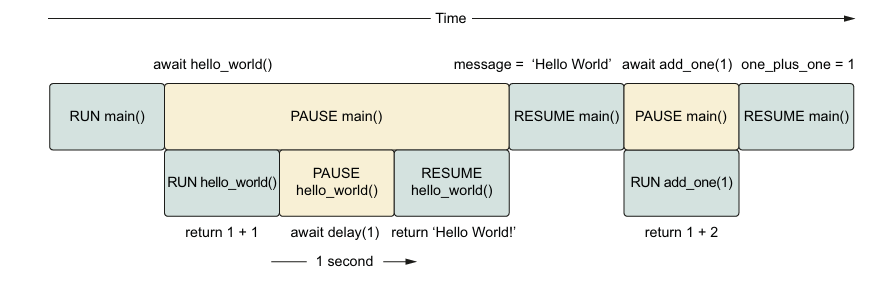

case. This behavior is illustrated in figure

We can see that the main coroutine is paused for 1 second while hello_world_

Both main and hello_world paused while we wait for delay(1) to finish. After it has

finished, main resumes and can execute add_one.

We’d like to move away from this sequential model and run add_one concurrently

with hello_world. To achieve this, we’ll need to introduce a concept called tasks.

## 2.5 Running concurrently with task

In Python's `asyncio`, you can create tasks to run code concurrently. This is done using the `asyncio.create_task` function. When you create a task, it starts running in the background immediately, allowing your program to do other things while waiting for the task to finish.

---

### Key Points:

1. **Creating a Task**:

- Use `asyncio.create_task()` with a coroutine function as its input.

- It returns a *task object* instantly.

2. **Awaiting a Task**:

- You can use `await` with the task object to pause your program until the task is done and get its result.

3. **Why Use Tasks?**

- Tasks allow other parts of your program to run without waiting for one operation to finish.

---

### Code Example: Creating and Using a Task

```python

import asyncio

from util import delay # A custom function that simulates a delay

async def main():

# Create a task that takes 3 seconds to complete

sleep_for_three = asyncio.create_task(delay(3))

# Immediately print the type of the task object

print(f"Task type: {type(sleep_for_three)}")

# Wait for the task to finish and get the result

result = await sleep_for_three

print(f"Task result: {result}")

# Run the main coroutine

asyncio.run(main())

```bash

---

### What’s Happening in the Code:

1. **Task Creation**:

- `asyncio.create_task(delay(3))` creates a task to run the `delay(3)` coroutine in the background.

- The task is of type ``, which is different from a regular coroutine.

2. **Running Concurrently**:

- After creating the task, the program does not wait for the task to finish.

- The `print()` statement runs immediately after the task is created.

3. **Waiting for the Task**:

- The `await sleep_for_three` line pauses the `main` coroutine until the task finishes.

- Once the task is complete, it returns its result, which is printed.

---

### Why Await is Important:

If you don’t use `await` on a task, it might not get enough time to finish. When the `asyncio.run` function exits, the event loop stops, and any unfinished tasks are “cleaned up” without completing. Using `await` ensures the task has a chance to finish.

> Note : When we create task using `asyncio.create_task` it run the task immediately in the background. It does not wait for the task to finish and immediately return a task object such that our program can do other things while waiting for the task to finish.We can use `await` later on to pause the program until the task is done and get its result.

# 2.6 Running multiple tasks concurrently

Given that tasks are created instantly and are scheduled to run as soon as possible, this

allows us to run many long-running tasks concurrently. We can do this by sequentially

starting multiple tasks with our long-running coroutine.

``` python

import asyncio

from util.delay_functions import delay

async def main():

# Create two tasks that take 3 seconds to complete

sleep_for_three=asyncio.create_task(delay(3))

sleep_again=asyncio.create_task(delay(3))

sleep_once_more=asyncio.create_task(delay(3))

await sleep_for_three

await sleep_again

await sleep_once_more

asyncio.run(main())

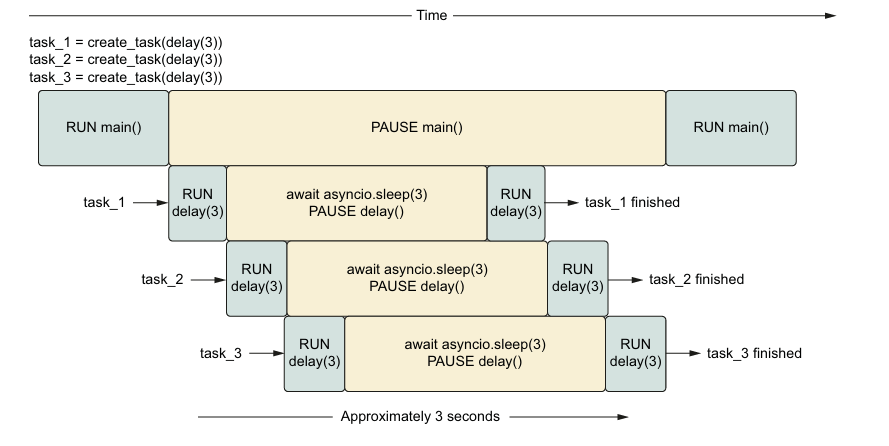

In this code, we create three tasks that each sleep for 3 seconds. We then await each task in sequence. This will cause each task to run concurrently, and the total time to complete will be around 3 seconds, not 9 seconds. This is because we are not waiting for each task to finish before starting the next one. Lets breakdown

Starting Three Tasks:

- The program begins by creating three tasks, each of which takes 3 seconds to complete.

- The

create_taskfunction starts the tasks immediately but doesn’t wait for them to finish—it just sets them up to run in the background.

The First Await Statement:

- When the code reaches the

await sleep_for_threeline, it pauses and gives control to the event loop. - This pause allows the event loop to check for any tasks waiting to run and starts them “as soon as possible.”

- When the code reaches the

Tasks Run Simultaneously:

- All three tasks begin running their

sleepoperations at the same time because the event loop handles them concurrently. - This concurrency allows the program to complete the work in 3 seconds instead of 9.

- All three tasks begin running their

Concurrency in Action:

- While the

sleepoperations run concurrently, any other code in the tasks (like print statements) runs one at a time, not simultaneously. - This means only the parts of the tasks that involve waiting (like sleeping) are parallelized.

- While the

Time Saved:

- If the tasks were executed one after another, the program would take 9 seconds (3 seconds × 3 tasks).

- By running the tasks concurrently, the program finishes in just 3 seconds, saving a lot of time.

This is illustrated in figure

NOTE This benefit compounds as we add more tasks; if we had launched 10 of these tasks, we would still take roughly 3 seconds, giving us a 10-fold speedup. This is the power of concurrency in asyncio.

asyncio.gather function

Gather function is a quick way to run multiple tasks concurrently and wait for all of them to complete. It takes in an iterable of awaitables and returns a single awaitable that will yield results in the order they were created. This is useful when we want to run multiple tasks concurrently and wait for all of them to finish before proceeding.

import asyncio

from util.delay_functions import delay

async def main():

# Create three tasks that take 3 seconds to complete and handel using asyncio.gather

results = await asyncio.gather(

delay(3),

delay(3),

delay(3)

)

print(results)

asyncio.run(main())

Note : For understanding You can use this logic . There is a task queue and event loop. When we only await coroutine there is only one task in the task queue and event loop .

coroutine need to await for running the task i.e keep in the task queue and eventloop if we directly run coroutine it will just give us coroutine object.

When we use asyncio.createtask() there are as much task in the task queue as the number of tasks created and event loop will run all the tasks concurrently also when we await new coroutine it will be added to the task queue and event loop will run it concurrently.

It return a task object instantly and run all the task concurrently i.e keep in the task queue and event loop without awaiting but does not wait for the task to finish it need to be awaited to get the proper result.

When we use asyncio.gather() it will run all the tasks concurrently and wait for all of them to finish before proceeding.

It need to be awaited to keep all the task in the task queue and event loop and wait for all of them to finish before proceeding.After finishing all the task it will return the result in the order they were created and jump to the next line of code of the main coroutine.

3. Synchronization Premitives

- Locks

- Semaphores

3.1 Locks

Locks are a synchronization primitive that allows us to limit access to a shared resource to only one coroutine at a time. This is useful when we have a resource that can only be accessed by one coroutine at a time, like a file or a database connection. Locks are created using the asyncio.Lock class and can be acquired using the acquire method and released using the release method.

#basic example of lock

import asyncio

async def locking(lock):

print('Waiting for the lock')

async with lock:

print('Acquired the lock')

await asyncio.sleep(2)

print('Released the lock')

async def main():

lock = asyncio.Lock()

await asyncio.gather(

locking(lock),

locking(lock),

locking(lock)

)

asyncio.run(main())

Output:

Waiting for the lock

Acquired the lock

Waiting for the lock

Waiting for the lock

Released the lock

Acquired the lock

Released the lock

Acquired the lock

Released the lock

In this example, we create a lock using asyncio.Lock and pass it to the locking coroutine. We then use the async with statement to acquire the lock and release it when we are done. When we run the program, we can see that only one coroutine can acquire the lock at a time, and the other coroutines have to wait until the lock is released.

3.2 Semaphores

Semaphores are a synchronization primitive that allows us to limit access to a shared resource to a fixed number of coroutines at a time. This is useful when we have a resource that can be accessed by a limited number of coroutines, like a connection pool or a web API. Semaphores are created using the asyncio.Semaphore class and can be acquired using the acquire method and released using the release method.

#basic example of semaphore

import asyncio

async def semaphoring(semaphore):

async with semaphore:

print('Acquired the semaphore')

await asyncio.sleep(2)

print('Released the semaphore')

async def main():

semaphore = asyncio.Semaphore(2)

await asyncio.gather(

semaphoring(semaphore),

semaphoring(semaphore),

semaphoring(semaphore),

semaphoring(semaphore)

)

asyncio.run(main())

Output:

Acquired the semaphore

Acquired the semaphore

Acquired the semaphore

Released the semaphore

Released the semaphore

Released the semaphore

Acquired the semaphore

Released the semaphore

In this example, we create a semaphore with a limit of 2 using asyncio.Semaphore and pass it to the semaphoring coroutine. We then use the async with statement to acquire the semaphore and release it when we are done. When we run the program, we can see that only two coroutines can acquire the semaphore at a time, and the other coroutines have to wait until the semaphore is released.

Some popular asyncio libraries

- aiohttp: An HTTP client and server library for asyncio.

- fastapi: A modern web framework for building APIs with Python 3.6+ based on standard Python type hints.

- aiofiles: A file operations library for asyncio.